New Test Bed Probes the Origin of Pulses at LCLS

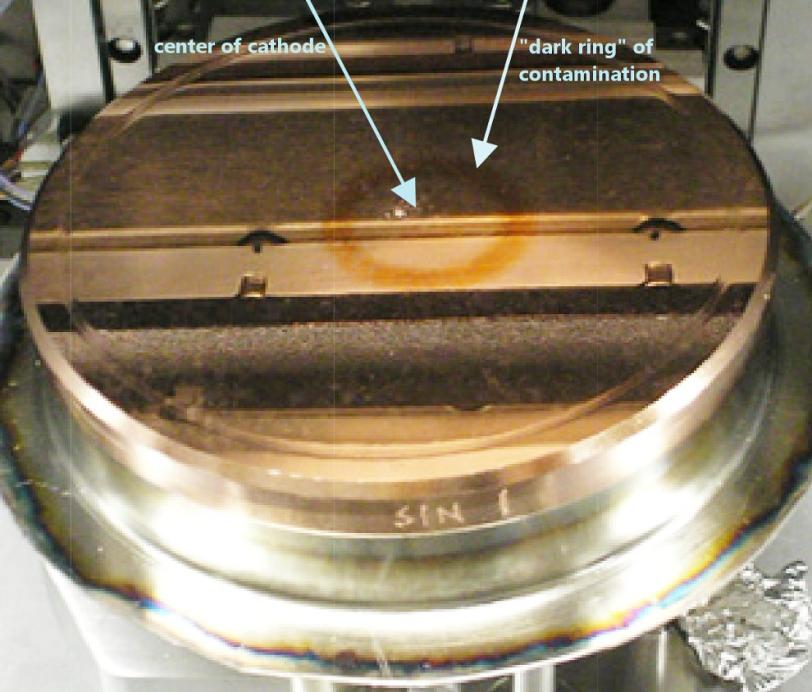

It all comes down to one tiny spot on a diamond-cut, highly pure copper plate.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

It all comes down to one tiny spot on a diamond-cut, highly pure copper plate. That's where every X-ray laser pulse at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source gets its start. That tiny spot must be close to perfect or it can impair and even halt LCLS operations.

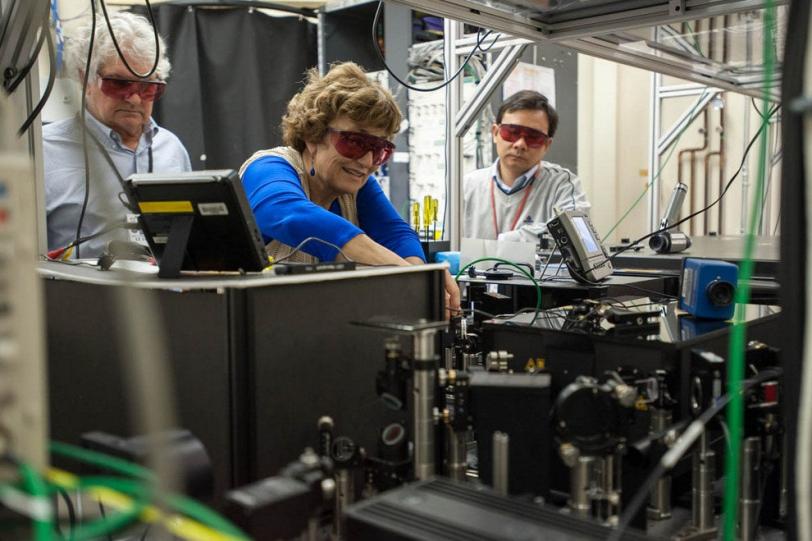

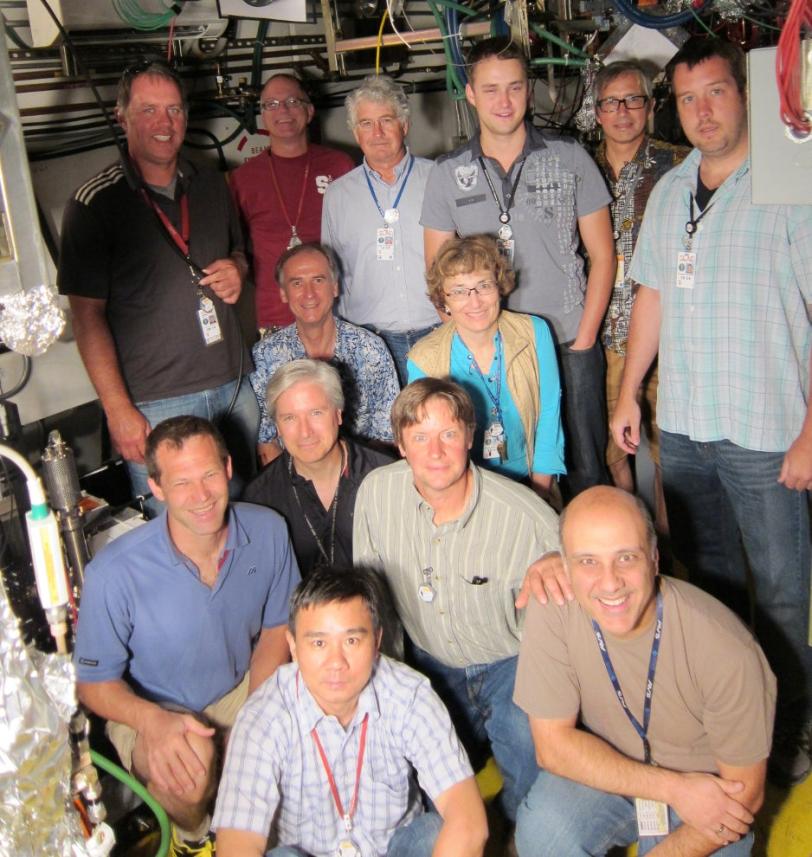

SLAC in May 2013 opened a new test facility at the Accelerator Structure Test Area (ASTA) to study the complex physics and chemistry that cause that shiny copper slab, called a cathode, to degrade over time, and to identify ways to maintain and improve its performance.

"ASTA is the ideal place, the perfect place to test the cathode, RF (radio-frequency) gun and the laser for the future demands of LCLS and LCLS-II, the planned upgrade of LCLS," said Feng Zhou, a SLAC physicist who has served since March 2013 as a project leader for cathode research and development at ASTA.

Zhou added, "Understanding cathode performance and degradation has been kind of a black art, and ASTA will for the first time allow very detailed analysis aimed at maximizing performance and longevity."

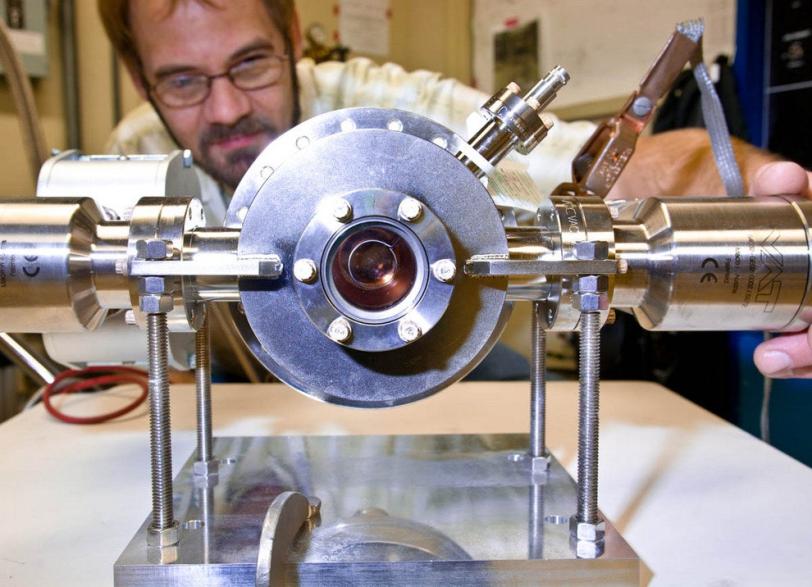

The copper cathode is part of the photocathode gun, the first step in a mile-long chain of precisely tuned equipment that makes up the LCLS. In the photocathode gun, a rapid-fire ultraviolet laser strikes a millimeter-size spot on the cathode. This generates tight bunches of electrons that are accelerated in a 1-kilometer section of SLAC's linear accelerator. The electrons then travel through a series of magnets, called an undulator, and emit ultrabright X-ray light that travels to LCLS experimental stations at a rate of more than 100 pulses per second.

Troubles with the LCLS cathode, including technical issues that required change-out of a cathode about two years ago, sparked SLAC's push for the cathode test bed, said Erik Jongewaard, a lead engineer for the project and former project leader who oversaw the construction of the test facility at ASTA.

"We couldn't get enough charge out of the cathode," said Jongewaard, "so there was a huge amount of emphasis – a lot of work by a lot of folks – looking at ways of getting around the problem." If the cathode does not produce sufficient electrons when struck by the ultraviolet laser pulses, the intensity of X-ray pulses will be limited.

Using a higher-intensity laser beam to "clean" the surface of the cathode has proven effective but requires more study.

"We want to understand the laser-cleaning process and also try to make sure this technique is robust. We also want to know the technique's limitations, and what is the optimum 'recipe,'" said Zhou.

Jongewaard said, "There may be a delicate balancing act in how much laser cleaning the surface can take before the cleaning itself damages the cathode." ASTA will enable precise measurements of how the cleaning improves or degrades the performance of each electron bunch.

ASTA will likely be used to study specialized coatings and determine whether they improve and extend the cathode's performance, too, and to test new ways to replace aging cathodes that minimize LCLS downtime.

Increasing the repetition rate of LCLS pulses, which would multiply the amount of data collected in experiments, will require advances in cathode, laser and RF gun systems, as well as in related RF systems. Such upgrades could be tested at ASTA.

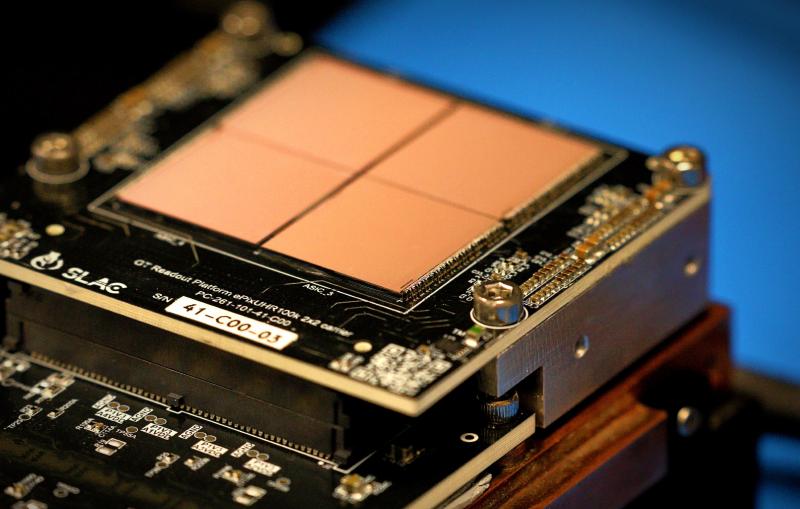

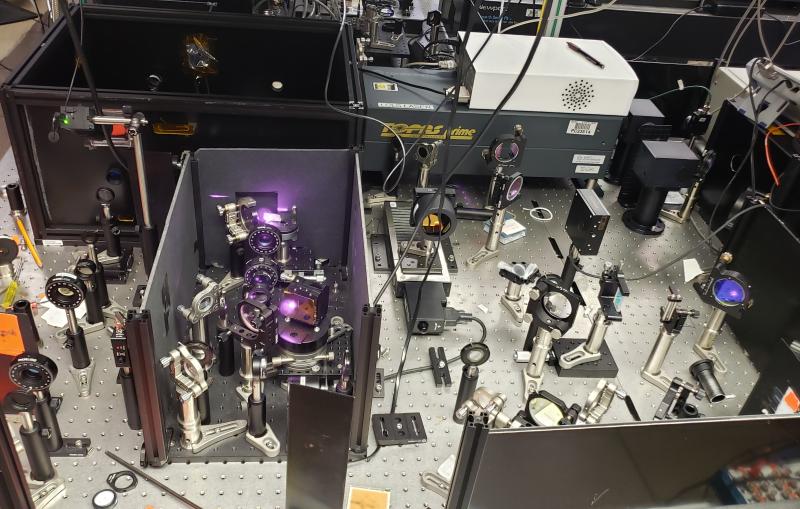

A range of sensors at ASTA will study the properties of the electrons produced with the photocathode guns, the effectiveness of the laser system that drives the electron bunches and the chemistry at the surface of the cathodes.

The drive laser system used for photocathode gun research at ASTA will also be used in a separate effort to develop laser techniques for echo-enabled harmonic generation, which can produce highly tunable X-ray laser pulses.

Ryan Coffee, an LCLS staff scientist, and others are also working on a new diagnostic tool, to be shared by both research programs, that can precisely measure the properties of ultraviolet laser pulses. This group had developed a similar tool to measure X-ray laser pulses. Coffee said the laser system at ASTA has already been upgraded to provide more flexibility for a range of experiments benefiting both efforts. "Everybody wins," he said.

Jongewaard said ASTA could eventually serve as a hub for researchers from other labs to collaborate in testing cathodes and related components. "In some sense this could become a small user facility," he said.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.